Berkshire Hathaway Inc. (NYSE:BRK.A BRK.B) has been in the news recently as Goldman Sachs initiated coverage on the stock with a “Buy” rating and then Stifel Nicolaus & Co. followed with a “Sell.” It’s not often that the street gets so polarized about a stock, tending to the more tepid “Hold,” so I thought I’d set out the long and short arguments below.

Long

Goldman Sachs’s view is summarized as follows:

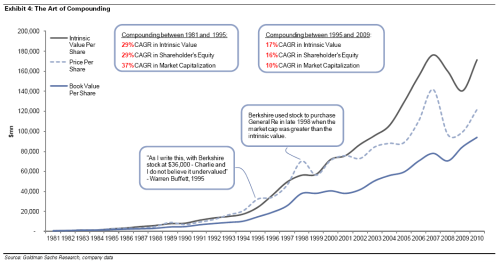

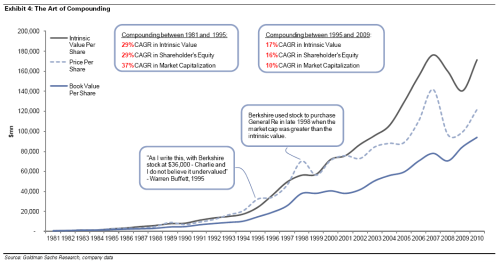

The best part of the Goldman analysis is their comparison of BRK market price to Goldman’s calculation of intrinsic value since 1981:

Click here to see Goldman Sachs’s BRK report.

Short

The short argument for BRK is described by Meyer Shields of Stifel Nicolaus & Co.. Shields’s view, from the WSJ’s Market Beat column, is as follows:

Greenbackd

http://greenbackd.com/

Long

Goldman Sachs’s view is summarized as follows:

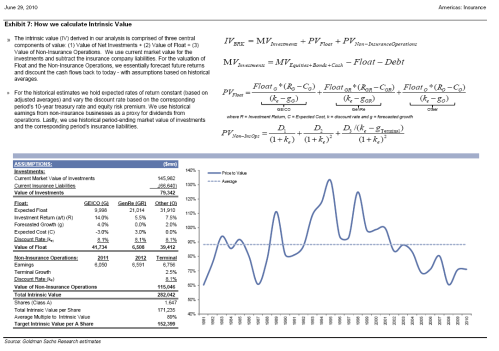

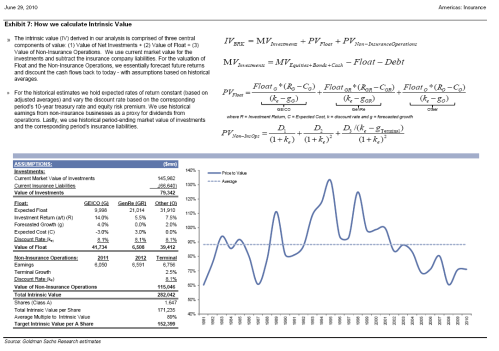

Valuation disconnect at a multi-decade highThe Goldman report also sets out Goldman’s rationale for calculating BRK intrinsic value with a very interesting back-test of the reasoning:

We initiate coverage of Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.A/BRK.B) with a Buy rating, as the disconnect between the market value of the stock and the intrinsic value of the business is close to a multi-decade high. With the recent inclusion of Berkshire in the S&P 500 and Russell indices and increased investor focus, we attempt to provide a framework for how to invest in the stock. In our view, the company is a unique collection of assets that over time earns a return on those assets – and as such should be valued accordingly.

Transformation: Key shifts in value mix

Post the acquisition of Burlington Northern, we estimate close to half of Berkshire’s intrinsic value will be derived from “operating” entities (as opposed to “securities investments”). This accomplishes two key things, in our view: (a) it reduces the long-term reliance on senior management’s equity investing decisions, and (b) provides greater clarity into the source of future value for the company as a whole.

Structural growth in largest segments

Structurally, Berkshire’s earnings will benefit from the ongoing shift in consumers’ auto insurance buying habits (via the direct-to-consumer GEICO subsidiary), the continuing change in the way goods are transported across the country (via the large intermodal operations at Burlington Northern), and the enduring growth in energy and power demand (via MidAmerican).

Levered to cyclical economic recovery

Cyclically, the non-insurance entities are tied to GDP growth and to a lesser extent, industrial production. Thus, as the economy continues to emerge from its cyclical downturn, we would expect earnings to grow at a faster rate than what appears to be currently discounted in the stock.

Price targets and risks

Our 12-month intrinsic value-based price target is $152,000 for BRK.A and $101 for BRK.B, implying over 25% upside. Key risks include an economic downturn, insured catastrophes, and management succession.

(1) Intrinsic ValueHere’s Goldman’s calculation of intrinsic value:

While Berkshire is a unique set of assets, we believe intrinsic value can be calculated in a manner similar to other companies. In our view the company is a collection of assets which earns a return on those assets over time – and thus the present value of such returns should equal the intrinsic value. Using historical drivers of returns (i.e. historical operating profits, market value of investments, interest rates, etc.) we can assess how Berkshire’s stock has tracked a derived intrinsic value over time. Importantly, however, the company has a long track record of producing significantly above-average returns on its assets and thus – while previous investment returns are no guarantee of future performance – we believe it is appropriate to factor above-average yields into intrinsic value. Specifically, we assess the intrinsic value as comprised of three main components:

1. The value of the investment portfolio (minus the insurance liabilities). This would be akin to a “book value” metric for other financial institutions. In other words, after liquidating the assets and having repaid all of the insurance obligations, the remainder would be the value left for shareholders.

2. The value of the float within the insurance operations. Float is the amount of funds an insurance company holds for future obligations and which can be invested for its own account. We ascribe a value to the float based on estimated future returns and growth. We will describe this analysis in more detail within the Insurance section below, however we would note this is the most unique component to the value of Berkshire, as there are few, if any, financial institutions with a track record of generating similar levels of consistent returns (see Exhibits 11-14 below).

3. The value of the non-insurance operating businesses. Outside of insurance, Berkshire owns majority stakes in a wide array of businesses. While the underlying operations are very diverse (i.e. railroads, utilities, carpet manufacturers, and even Dairy Queen), the businesses tend to share a common characteristic in that almost all maintain leading market share for either their industry or their geography. This is important when ascribing an intrinsic or long-term value to the operations, as the risk of obsolescence for the majority of the operations is considerably lower than other individual companies within the market. The idea of a real competitive advantage – or “moat” – suggests that at worst the companies will grow with the economy and at best will continue to compound returns at a rate higher than their peers. When valuing the non-insurance operations of Berkshire, we utilize a discounted cash flow model by aggregating expected earnings and applying a modest (and declining) 3-year growth rate and then a terminal growth rate of 2.5%.

Other key points to note:

- Historically, the majority of the value derived from Berkshire has been sourced from the insurance operations – i.e. components one and two above. However, post the Burlington Northern acquisition, the contribution from non-insurance earnings will be larger than at any previous time in BRK’s history. We believe this is likely a concerted effort by current management over the past few years to allow for the “investing” component of BRK’s value to become less of a variable in the future – and thereby reducing the risk of lower investment returns impacting the value of Berkshire in the future (see Exhibits 5 and 6 below).

- When we back-test our intrinsic value (as seen in Exhibit 4 above), we can show that comments or actions (as highlighted in the exhibit) made by Berkshire are consistent with the relationship depicted between intrinsic value and the market value ascribed to Berkshire stock. For example, in 1998, when Berkshire purchased General Re with stock, our analysis clearly shows the market value of the stock exceeded the intrinsic value of the company – thus, making the acquisition with “share currency” a significant value addition to the overall shares (ignoring however the future liability problems that General Re wound up disclosing).

- When we back-test our intrinsic value model, we use a market cost of equity – i.e. the 10-year risk free rate and an applied equity risk premium for the US stock market. Not surprisingly, the general declining cost of capital over the past 30 years has helped to raise the value of Berkshireas well as the market.

- While Berkshire can be shown to be largely impacted by cyclical industrial forces within the US, we note that the dual nature of the operations (i.e. insurance and non-insurance) allows for uncorrelated value creation opportunities. In other words, despite the recent recession’s negative impact on the future cash flows of the noninsurance businesses, the continued increase in insurance float (and the corresponding high-yielding investments made with that float) helped to mute the negative impact on the overall value of Berkshire.

The best part of the Goldman analysis is their comparison of BRK market price to Goldman’s calculation of intrinsic value since 1981:

Click here to see Goldman Sachs’s BRK report.

Short

The short argument for BRK is described by Meyer Shields of Stifel Nicolaus & Co.. Shields’s view, from the WSJ’s Market Beat column, is as follows:

Q: Meyer, thanks a lot for taking the time to parry a few of our questions. First things first, does it feel strange to hit the sell button on Buffett?[Full Disclosure: No positions. This is neither a recommendation to buy or sell any securities. All information provided believed to be reliable and presented for information purposes only. Do your own research before investing in any security.]

A: It does, because it sounds like I’m saying that I know more about investing or markets than Buffett does, which is nuts. All I’m saying is that I think the share price underperforms in the near-term.

Q: And from the looks of your note, you’re not saying that the Buffmeister has lost his edge. A lot of your analysis is about your outlook for the economy right? So, put simply: The slower the economy, the slower the results at all the multivarious businesses Berkshire owns?

A: With the exception of insurance, which is pretty well-insulated from the economy, yes. Berkshire’s more exposed to homebuilding and less exposed to technology than the overall economy, but the bottom line is that if unemployment stays high, spending stays low, both for the U.S. in general and Berkshire in particular.

Q: So, if a weak economy is bad for both Berkshire and the U.S. in general. Why would Berkshire underperform in the near-term?

A: On top of its own businesses’ exposure to the economy, Berkshire sold some equity index put options that are marked to market every quarter, so its book value gets hit twice.

Q: Ahah! So Berkshire sold puts — options that make money when the underlying falls in price. That means essentially Berkshire is on the hook to pay-up for the falloff we saw during the correction. Right?

A: Yes, except that it would only be on the hook for that sort of falloff if there’s no recovery until 2018 and beyond. In the meanwhile, the only issue is the mark-to-market, but in March 2009, that was enough to spook investors.

Q: Ah, ok. So, Berkshire is going to have to take a paper loss this quarter on those puts it sold. Got it. You note that Berkshire has been outperforming the S&P 500 by about 26% year-to-date. I’m wondering how much of that may have to do with the Baby Berks being added to the S&P 500? (A lot of index funds had to buy.) Wondering if you have any other thoughts on what Berkshire’s addition to the index might mean for the shares?

A: I think there were three implications of the addition to the S&P. First, a lot of funds had to buy the stock. Second, the resulting share price appreciation meant that it cost Buffett fewer Berkshire shares to purchase Burlington Northern. Third (and this is less positive), with widespread professional ownership, the “cult-stock” aspect (some investors use valuation methods for Berkshire that don’t work for any other name) will weaken, making the shares more “normal.”

Q: Interesting. You mean “cult,” like, less of the long-term loyalists that stick with the stock through thick and thin?

A: Exactly. I think we’ll see bigger reactions to good and bad quarters than we’ve seen in the past.

Q: Good stuff. Thanks a lot for taking the time. We’ll be watching to see how the call pans out. We’d wish you good luck, but then some of Buffett’s cult following might attack us in the comments section, and accuse us of anti-Buffett bias. So, we’ll just wish you a generalized, not-specific-to-this-call, good luck.

A: I love Warren Buffett, and I look forward to the stock trading down to a point where I can rate it a Buy.

Greenbackd

http://greenbackd.com/