Yesterday, I examined Aswath Damodaran’s paper ”Value Investing: Investing for Grown Ups?” in which Damodaran asked, “If value investing works, why do value investors underperform?”

Damodaran divides the value world into three groups:

The Contrarian Value Investors

Buying losers seems to work over a long time scale.

Damodaran:

Weird. The winner portfolio actually outperforms the loser portfolio in the first 12 months. Says Damodaran:

A more sophisticated version of contrarian value investing is buying “unexcellent” companies and selling “excellent” companies. Damodaran’s rationale is as follows:

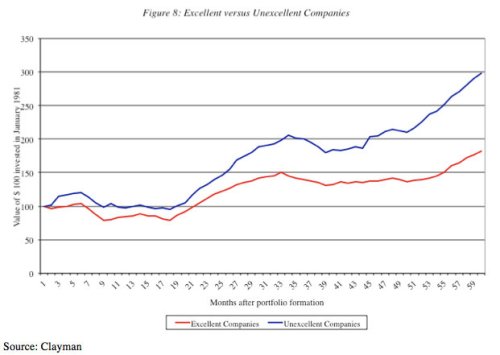

Clearly, “Excellent companies” are excellent, and “Unexcellent companies” suck (negative return on equity!). Confronted with the choice to invest in one group of the other, it’s a no-brainer. Or is it? Here are the returns:

Ruh roh. Says Damodaran:

Looks like a pretty clear inverse relationship between rating and return. Sure, whereof rating, thereof “risk,” but I’m prepared to wear that “risk” for the return.

So contrarian value investing works. How do we mess this up?

Damodaran divides the value world into three groups:

- “The Passive Screeners,” – “The Graham approach to value investing is a screening approach, where investors adhere to strict screens… and pick stocks that pass those screens.”

- “The Contrarian Value Investors,” – “In this manifestation of value investing, you begin with the belief that stocks that are beaten down because of the perception that they are poor investments (because of poor investments, default risk or bad management) tend to get punished too much by markets just as stocks that are viewed as good investments get pushed up too much.”

- “Activist value investors,” – “The strategies used by …[activist value investors] are diverse, and will reflect why the firm is undervalued in the first place. If a business has investments in poor performing assets or businesses, shutting down, divesting or spinning off these assets will create value for its investors. When a firm is being far too conservative in its use of debt, you may push for a recapitalization (where the firm borrows money and buys back stock). Investing in a firm that could be worth more to someone else because of synergy, you may push for it to become the target of an acquisition. When a company’s value is weighed down because it is perceived as having too much cash, you may demand higher dividends or stock buybacks. In each of these scenarios, you may have to confront incumbent managers who are reluctant to make these changes. In fact, if your concerns are broadly about management competence, you may even push for a change in the top management of the firm.”

The Contrarian Value Investors

Buying losers seems to work over a long time scale.

Damodaran:

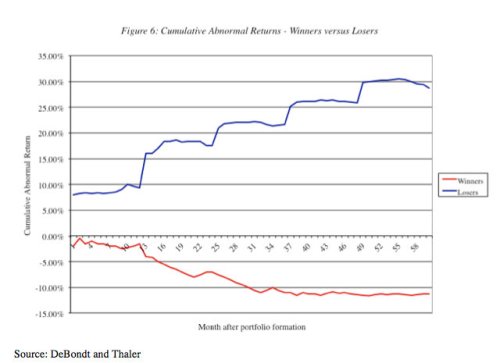

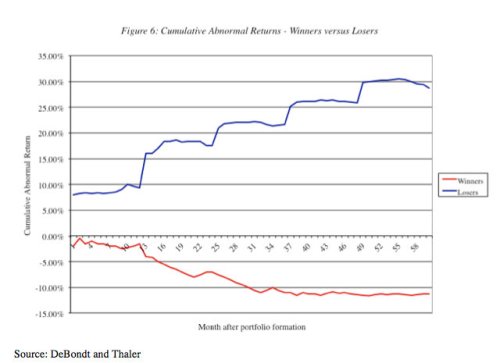

This analysis suggests that an investor who bought the 35 biggest losers over the previous year and held for five years would have generated a cumulative abnormal return of approximately 30% over the market and about 40% relative to an investor who bought the winner portfolio.Several select caveats:

This evidence is consistent with market overreaction and suggests that a simple strategy of buying stocks that have gone down the most over the last year or years may yield excess returns over the long term. Since the strategy relies entirely on past prices, you could argue that this strategy shares more with charting – consider it a long term contrarian indicator – than it does with value investing.

• Studies also seem to find loser portfolios created every December earn significantly higher returns than portfolios created every June. This suggests an interaction between this strategy and tax loss selling by investors. Since stocks that have gone down the most are likely to be sold towards the end of each tax year (which ends in December for most individuals) by investors, their prices may be pushed down by the tax loss selling.Damodaran’s final point above – that price momentum works over short periods – is interesting:

• There seems to be a size effect when it comes to the differential returns. When you do not control for firm size, the loser stocks outperform the winner stocks, but when you match losers and winners of comparable market value, the only month in which the loser stocks outperform the winner stocks is January.21

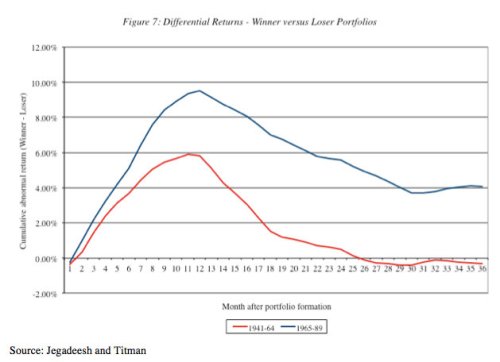

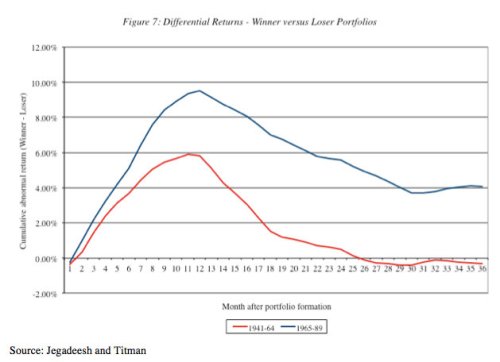

• The final point to be made relates to time horizon. There may be evidence of price reversals in long periods (3 to 5 years) and there is the contradictory evidence of price momentum– losing stocks are more likely to keep losing and winning stocks to keep winning – if you consider shorter periods (six months to a year). An earlier study that we referenced, by Jegadeesh and Titman tracked the difference between winner and loser portfolios by the number of months that you held the portfolios.22

Weird. The winner portfolio actually outperforms the loser portfolio in the first 12 months. Says Damodaran:

[L]oser stocks start gaining ground on winning stocks after 12 months, [but] it took them 28 months in the 1941-64 time period to get ahead of them and the loser portfolio does not start outperforming the winner portfolio even with a 36-month time horizon in the 1965-89 time period. The payoff to buying losing companies may depend heavily on whether you have to capacity to hold these stocks for long time periods.Bad companies can be good investments

A more sophisticated version of contrarian value investing is buying “unexcellent” companies and selling “excellent” companies. Damodaran’s rationale is as follows:

If you are right about markets overreacting to recent events, expectations will be set too high for stocks that have been performing well and too low for stocks that have been doing badly. If you can isolate these companies, you can buy the latter and sell the former.Take note, franchise investors:

Any investment strategy that is based upon buying well-run, good companies and expecting the growth in earnings in these companies to carry prices higher is dangerous, since it ignores the possibility that the current price of the company already reflects the quality of the management and the firm. If the current price is right (and the market is paying a premium for quality), the biggest danger is that the firm loses its luster over time, and that the premium paid will dissipate. If the market is exaggerating the value of the firm, this strategy can lead to poor returns even if the firm delivers its expected growth. It is only when markets under estimate the value of firm quality that this strategy stands a chance of making excess returns.The tale of Tom Peters’s In Search of Excellence:

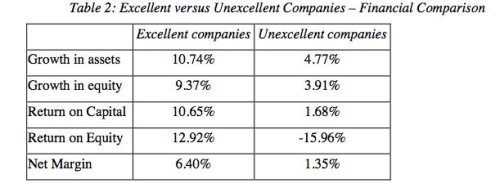

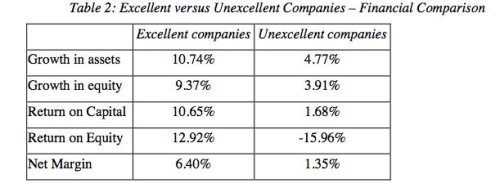

There is some evidence that well managed companies do not always make good investments. Tom Peters, in his widely read book on excellent companies a few years ago, outlined some of the qualities that he felt separated excellent companies from the rest of the market.23 Without contesting his standards, a study went through the perverse exercise of finding companies that failed on each of the criteria for excellence – a group of unexcellent companies and contrasting them with a group of excellent companies.Here’s a statistical comparison of the two groups:

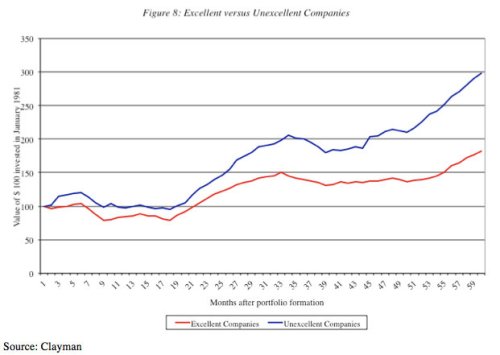

Clearly, “Excellent companies” are excellent, and “Unexcellent companies” suck (negative return on equity!). Confronted with the choice to invest in one group of the other, it’s a no-brainer. Or is it? Here are the returns:

Ruh roh. Says Damodaran:

The excellent companies may be in better shape financially but the unexcellent companies would have been much better investments at least over the time period considered (1981-1985). An investment of $ 100 in unexcellent companies in 1981 would have grown to $ 298 by 1986, whereas $ 100 invested in excellent companies would have grown to only $ 182. While this study did not control for risk, it does present some evidence that good companies are not necessarily good investments, whereas bad companies can sometimes be excellent investments.A legitimate criticism of this study is that the time period is very short (5 years) and may be an aberration – it began, after all, right at the end of a tough bear market, where any stock with the fundamentals of the unexcellent companies would have looked like poison. How about a second study?

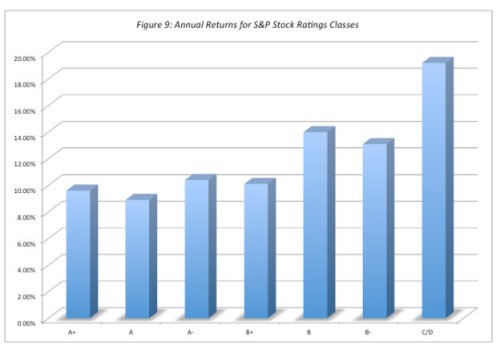

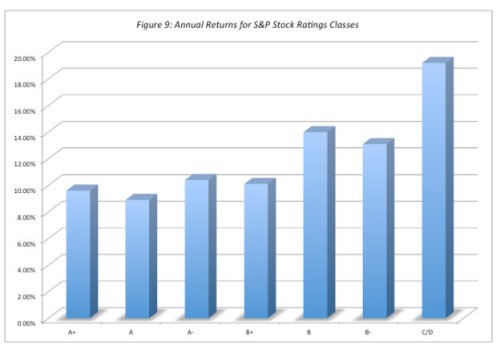

The second study used a more conventional measure of company quality. Standard and Poor’s, the ratings agency, assigns quality ratings to stocks that resemble its bond ratings. Thus, an A rated stock, according to S&P, is a higher quality investment than a B+ rated stock, and the ratings are based upon financial measures (such as profitability ratios and financial leverage). Figure 9 summarizes the returns earned by stocks in different ratings classes, and as with the previous study, the lowest rated stocks had the highest returns and the highest rated stocks had the lowest returns.And here are the returns:

Looks like a pretty clear inverse relationship between rating and return. Sure, whereof rating, thereof “risk,” but I’m prepared to wear that “risk” for the return.

So contrarian value investing works. How do we mess this up?

a. Long Time Horizon: To succeed by buying these companies, you need to have the capacity to hold the stocks for several years. This is necessary not only because these stocks require long time periods to recover, but also to allow you to spread the high transactions costs associated with these strategies over more time. Note that having a long time horizon as a portfolio manager may not suffice if your clients can put pressure on you to liquidate holdings at earlier points. Consequently, you either need clients who think like you do and agree with you, or clients that have made enough money with you in the past that their greed overwhelms any trepidation they might have in your portfolio choices.Tomorrow, the activists.

b. Diversify: Since poor stock price performance is often precipitated or accompanied by operating and financial problems, it is very likely that quite a few of the companies in the loser portfolio will cease to exist. If you are not diversified, your overall returns will be extremely volatile as a result of a few stocks that lose all of their value. Consequently, you will need to spread your bets across a large number of stocks in a large number of sectors. One variation that may accomplish this is to buy the worst performing stock in each sector, rather than the worst performing stocks in the entire market.

c. Personal qualities: This strategy is not for investors who are easily swayed or stressed by bad news about their investments or by the views of others (analysts, market watchers and friends). Almost by definition, you will read little that is good about the firms in your portfolio. Instead, there will be bad news about potential default, management turmoil and failed strategies at the companies you own. In fact, there might be long periods after you buy the stock, where the price continues to go down further, as other investors give up. Many investors who embark on this strategy find themselves bailing out of their investments early, unable to hold on to these stocks in the face of the drumbeat of negative information. In other words, you need both the self-confidence to stand your ground as others bail out and a stomach for short-term volatility (especially the downside variety) to succeed with this strategy.