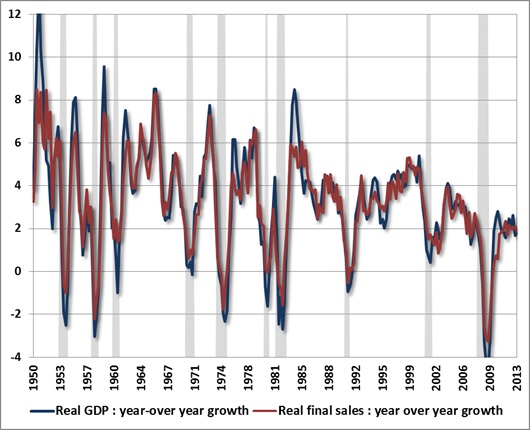

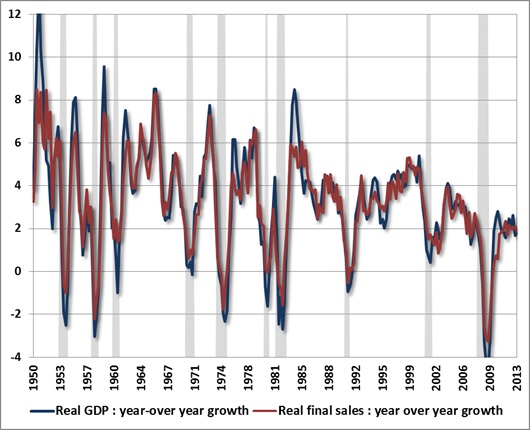

The advance estimate for first quarter GDP came in decidedly below expectations at a 2.5% annual rate, but even that rate belies the fact that real final sales slowed to just 1.5% growth, from 1.8% last quarter. The remaining 1% of the first-quarter growth figure – 40% of the total – represented the accumulation of unsold inventory. My view remains that the U.S. is unlikely to avoid joining the rest of the developed world in a global recession that is already underway, and may well be already underway in the U.S. once data revisions are reflected. The year-over-year growth rates of real GDP and real final sales have declined to just 1.80% and 1.87% respectively, which is the first time in this economic cycle that both have simultaneously declined from above 2.0% to below 1.9% - an occurrence that has been a hallmark of every post-war recession, with remarkably few false signals for such a simple measure. The Fed’s ability to kick-the-can in increments of a few months at a time may allow this time to be different, but investors should recognize that they are relying on that proposition.

It is certainly not the case that economic recessions precisely overlap with bear markets. Rather, bear markets are frequently underway before recessions are evident, and typically end several months before the recessions do. For that reason, market returns aren’t reliably abysmal when measured from the very start of a recession to its very end. Even so, note the shaded recessions in the chart below. Bear markets in equities occurred in 1956, 1961, 1970, 1973-74, 1981-82, 1990, 2000-02, and 2007-09. Of course, there are many less severe but still damaging market declines that occurred in the absence of recession.

Meanwhile, early evidence shows a very uniform deterioration in regional surveys of economic activity, with the Philadelphia Fed, Richmond Fed, and Empire Manufacturing surveys experiencing unanimous declines in overall activity, new orders and order backlogs in the April reports. The coming week will bring data from the Dallas Fed, Chicago and national surveys from the Institute of Supply Management, a Fed statement on Wednesday, and an employment report on Friday. Even deep-seated fundamentals have not always resolved into immediate outcomes in recent years, so I have no particular confidence about the direction of these reports. It’s just that nothing in the data is suggestive of a durable shift toward stronger economic activity.

...

Albert Edwards at SocGen is not optimistic. Last week, he reiterated his concern that the S&P 500 would ultimately establish a low at 450. There is not a missing “1” in front of that figure. At first glance, 450 on the S&P seems absolutely preposterous, as Wall Street will be quick to point out that operating earnings are estimated to be over $110 this year, and a level of 450 would imply a P/E ratio of less than 4.5. But interestingly, if one corrects for the fact that profit margins are more than 70% above their historical norms, and that any recession in the coming years would be likely to draw "forward earnings" estimates to the $70-80 range, Albert’s estimate works out to a forward P/E of about 6 – which again seems low, until you impute forward earnings historically, and realize that the pre-bubble norm for the forward P/E has typically been less than 11, while secular lows have occurred at what would have indeed been forward P/E ratios right about 6 (see the August 2007 comment - Long Term Evidence on the Fed Model and Forward Operating P/E Ratios).

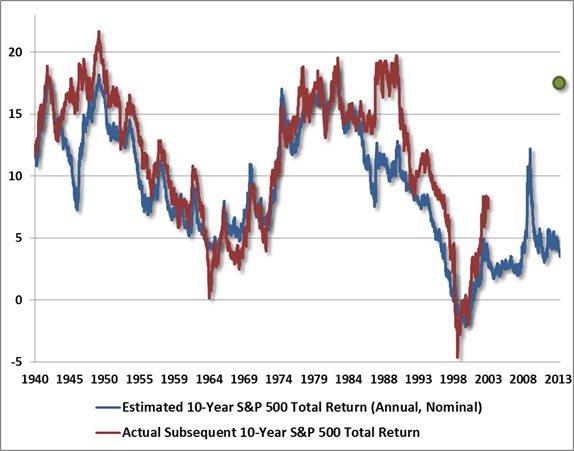

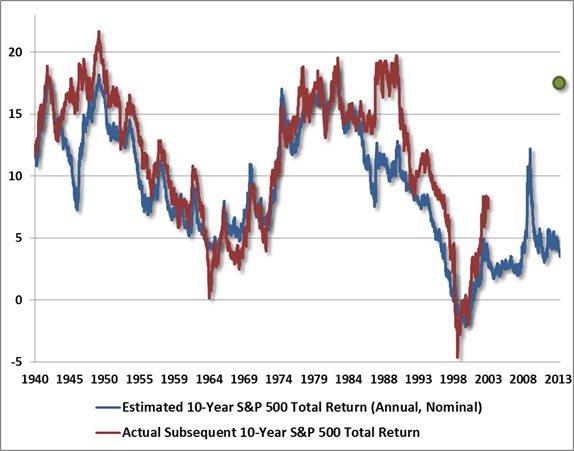

When we take Albert’s target to our own valuation approach, a move to 450 on the S&P 500 would drive our own estimates of 10-year prospective S&P 500 returns to about 18% annually, which is certainly higher than we observed in 2009, but is disturbingly right in line with the valuations that have typically been established with durable secular lows.

For our part, nothing in our own approach requires more than a moderate retreat in valuations to warrant a constructive investment position (provided that our measures of market action are favorable and overvalued, overbought, overbullish syndromes are absent). Over the complete market cycle, I believe that the best investment approach is to accept market risk in proportion to the estimated return/risk profile that is associated with any prevailing set of market conditions – and those conditions include not only valuations, but market action, trend-following measures, sentiment, yes – monetary conditions, and other factors.

Read the complete commentary

It is certainly not the case that economic recessions precisely overlap with bear markets. Rather, bear markets are frequently underway before recessions are evident, and typically end several months before the recessions do. For that reason, market returns aren’t reliably abysmal when measured from the very start of a recession to its very end. Even so, note the shaded recessions in the chart below. Bear markets in equities occurred in 1956, 1961, 1970, 1973-74, 1981-82, 1990, 2000-02, and 2007-09. Of course, there are many less severe but still damaging market declines that occurred in the absence of recession.

Meanwhile, early evidence shows a very uniform deterioration in regional surveys of economic activity, with the Philadelphia Fed, Richmond Fed, and Empire Manufacturing surveys experiencing unanimous declines in overall activity, new orders and order backlogs in the April reports. The coming week will bring data from the Dallas Fed, Chicago and national surveys from the Institute of Supply Management, a Fed statement on Wednesday, and an employment report on Friday. Even deep-seated fundamentals have not always resolved into immediate outcomes in recent years, so I have no particular confidence about the direction of these reports. It’s just that nothing in the data is suggestive of a durable shift toward stronger economic activity.

...

Albert Edwards at SocGen is not optimistic. Last week, he reiterated his concern that the S&P 500 would ultimately establish a low at 450. There is not a missing “1” in front of that figure. At first glance, 450 on the S&P seems absolutely preposterous, as Wall Street will be quick to point out that operating earnings are estimated to be over $110 this year, and a level of 450 would imply a P/E ratio of less than 4.5. But interestingly, if one corrects for the fact that profit margins are more than 70% above their historical norms, and that any recession in the coming years would be likely to draw "forward earnings" estimates to the $70-80 range, Albert’s estimate works out to a forward P/E of about 6 – which again seems low, until you impute forward earnings historically, and realize that the pre-bubble norm for the forward P/E has typically been less than 11, while secular lows have occurred at what would have indeed been forward P/E ratios right about 6 (see the August 2007 comment - Long Term Evidence on the Fed Model and Forward Operating P/E Ratios).

When we take Albert’s target to our own valuation approach, a move to 450 on the S&P 500 would drive our own estimates of 10-year prospective S&P 500 returns to about 18% annually, which is certainly higher than we observed in 2009, but is disturbingly right in line with the valuations that have typically been established with durable secular lows.

For our part, nothing in our own approach requires more than a moderate retreat in valuations to warrant a constructive investment position (provided that our measures of market action are favorable and overvalued, overbought, overbullish syndromes are absent). Over the complete market cycle, I believe that the best investment approach is to accept market risk in proportion to the estimated return/risk profile that is associated with any prevailing set of market conditions – and those conditions include not only valuations, but market action, trend-following measures, sentiment, yes – monetary conditions, and other factors.

Read the complete commentary