“It’s quite possible that even a small taper will be too much for investors, but the alternative to tapering is to make an already precarious situation more precarious, while damaging the Fed’s credibility in the process.”

Hussman Weekly Market Comment, Baby Steps, September 16, 2013

Last week, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) decided to go the alternative route. The Fed’s decision does not seem intended to be a “reset” of perpetual quantitative easing. Instead, it appears to reflect the committee’s belief that QE has real economic effects, but that these economic benefits have not gained sufficient momentum. Notably, one member of the FOMC who voted in favor observed on Friday that the decision not to reduce the pace of quantitative easing was a “borderline decision.” Another voiced concerns that the Fed now faces “challenges that come with issues of credibility” and that the inaction “discounts the potential costs of the policy tool with which we have limited experience.”

In my view, the problem with quantitative easing is that its entire effect relies on provoking risk-taking by those who would otherwise choose not to do so; that the FOMC has extended and amplified financial market distortions without regard to the rich valuations and dismal prospective returns that financial assets are most likely priced to achieve; and that this distortion of financial asset prices has precious little to do with the presumptive goal of Fed policy, which is greater job creation and economic activity.

Unfortunately, even though the equity market has been rising on what we view as nothing but noxious psychological ether, the FOMC has – perhaps unintentionally – released another tank of the stuff. Quantitative easing only “works” however, to the extent that investors have no immediate desire to hold short-term, risk-free assets. In any environment where investors become eager to hold currency and other low-risk, default-free assets despite their low yield, I expect that both investors and the Fed will discover that quantitative easing is wholly ineffective in supporting the prices of risky assets. This is an experiment that has not yet run its course, and we have no intention of being the guinea pigs in that study.

The challenge at present is that last week’s Fed’s decision does make an already precarious situation more precarious. So the question is how to respond. From the experience of the past few years, the risk is that enthusiasm that the Fed is “all-in” could prompt a surge of further speculation, and even greater financial distortions. At the same time, examining market cycles over a century of market history, present conditions cluster among the most negative 2-3% of data points in terms of average return and downside risk.

...

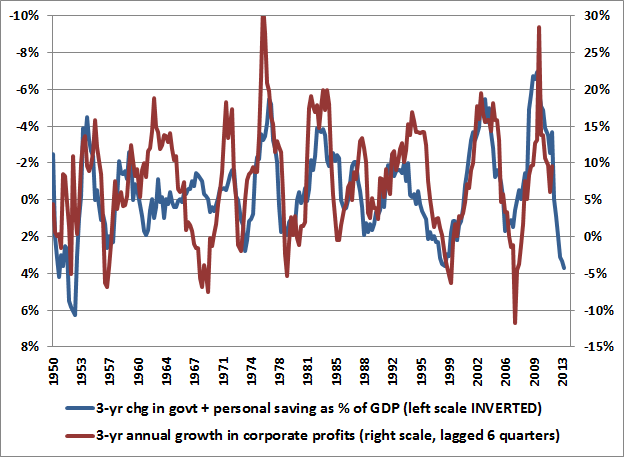

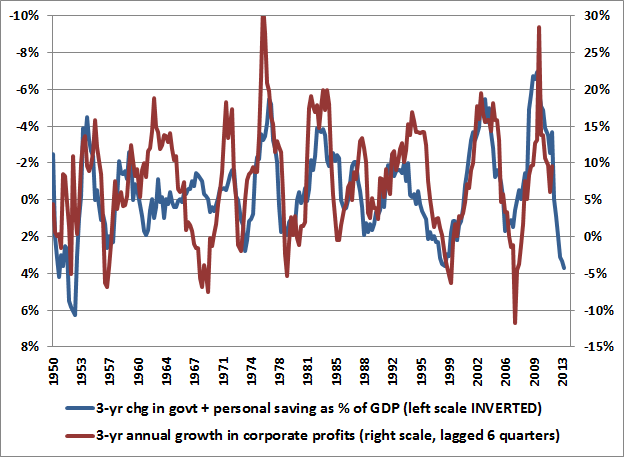

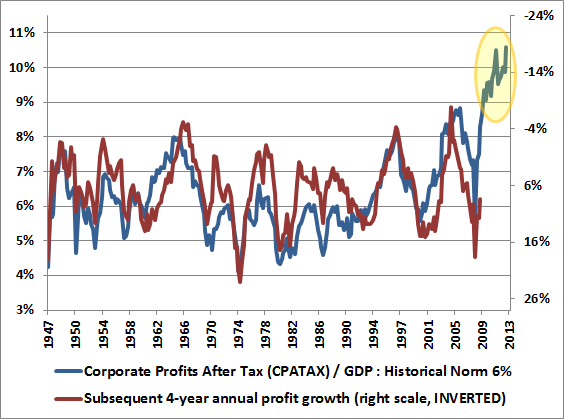

From the standpoint of long term stock market returns, the most important feature of valuations to note at present is the extreme level of profit margins, which are more than 70% higher than historical norms. This is well-explained by the fact that the deficits of one sector must, in equilibrium, emerge as the surplus of another sector. As has been consistently evident U.S. economic data across history, large deficits in the combined government and household sectors are invariably reflected in mirror-image surpluses in corporate profits, as a share of GDP. This is not only true in terms of levels but in terms of changes. That is, the change in combined government and household savings over periods of say, 3-4 years is also closely mirrored by changes in corporate profits in the opposite direction. This isn’t even a theory – it’s largely driven by accounting identities and economic equilibrium.

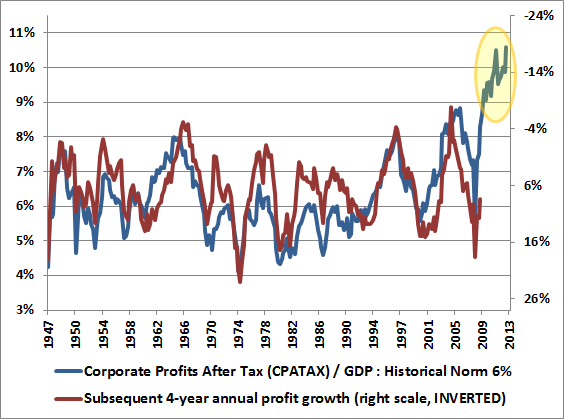

Again, the difficulty with valuing stocks on the basis of raw price/earnings ratios is that corporate profits as a share of GDP are presently over 70% above their long-term historical norm. Though the actual course of corporate profits will be affected by numerous factors, including the extent to which extraordinary fiscal deficits normalize, we would expect corporate profits over the coming 3-4 year period to contract at a rate of somewhere between 5-15% annually. The practice of valuing stocks on the basis of current earnings or Wall Street’s projections of “forward operating earnings” (which embed assumptions of even more extreme profit margins) hasnever in history been more reckless and misleading.

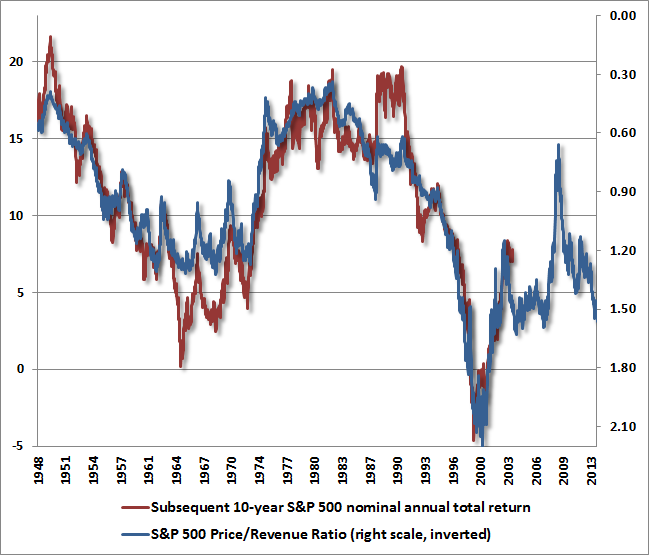

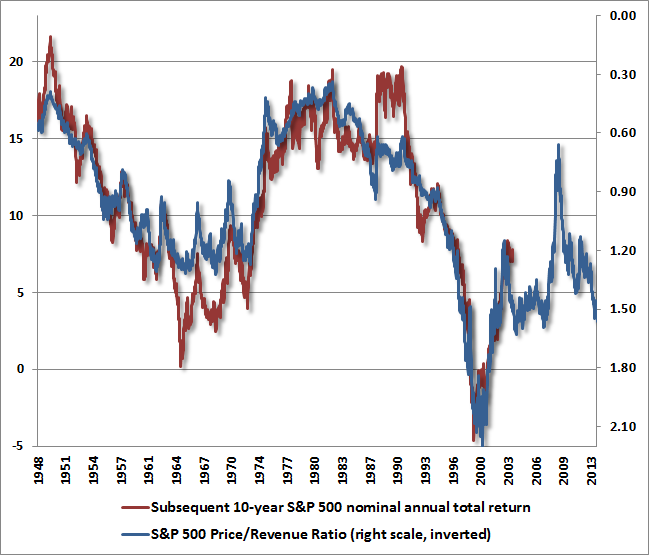

One hardly needs to accept any of these concerns to recognize that current equity valuations are consistent with the likelihood of dismal long-term returns. The historical record of reliable valuation measures should be sufficient. The chart below illustrates the relationship between the S&P 500 price/revenue ratio and subsequent 10-year nominal annual total returns for the S&P 500.

Last week, much was made of a remark by Warren Buffett that he was having difficulty finding any bargains in the current market. In our view, he did not go far enough, because even his more recent comments about valuation seem inconsistent with his own very accurate observations in the past. For example, Buffett noted in 1999 that “In my opinion, you have to be wildly optimistic to believe that corporate profits as a percent of GDP can, for any sustained period, hold much above 6%.” That assertion was clearly demonstrated by the clearly cyclical behavior of margins in the years that followed. It’s an assertion that deserves particular attention today.

Read the complete commentary

Hussman Weekly Market Comment, Baby Steps, September 16, 2013

Last week, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) decided to go the alternative route. The Fed’s decision does not seem intended to be a “reset” of perpetual quantitative easing. Instead, it appears to reflect the committee’s belief that QE has real economic effects, but that these economic benefits have not gained sufficient momentum. Notably, one member of the FOMC who voted in favor observed on Friday that the decision not to reduce the pace of quantitative easing was a “borderline decision.” Another voiced concerns that the Fed now faces “challenges that come with issues of credibility” and that the inaction “discounts the potential costs of the policy tool with which we have limited experience.”

In my view, the problem with quantitative easing is that its entire effect relies on provoking risk-taking by those who would otherwise choose not to do so; that the FOMC has extended and amplified financial market distortions without regard to the rich valuations and dismal prospective returns that financial assets are most likely priced to achieve; and that this distortion of financial asset prices has precious little to do with the presumptive goal of Fed policy, which is greater job creation and economic activity.

Unfortunately, even though the equity market has been rising on what we view as nothing but noxious psychological ether, the FOMC has – perhaps unintentionally – released another tank of the stuff. Quantitative easing only “works” however, to the extent that investors have no immediate desire to hold short-term, risk-free assets. In any environment where investors become eager to hold currency and other low-risk, default-free assets despite their low yield, I expect that both investors and the Fed will discover that quantitative easing is wholly ineffective in supporting the prices of risky assets. This is an experiment that has not yet run its course, and we have no intention of being the guinea pigs in that study.

The challenge at present is that last week’s Fed’s decision does make an already precarious situation more precarious. So the question is how to respond. From the experience of the past few years, the risk is that enthusiasm that the Fed is “all-in” could prompt a surge of further speculation, and even greater financial distortions. At the same time, examining market cycles over a century of market history, present conditions cluster among the most negative 2-3% of data points in terms of average return and downside risk.

...

From the standpoint of long term stock market returns, the most important feature of valuations to note at present is the extreme level of profit margins, which are more than 70% higher than historical norms. This is well-explained by the fact that the deficits of one sector must, in equilibrium, emerge as the surplus of another sector. As has been consistently evident U.S. economic data across history, large deficits in the combined government and household sectors are invariably reflected in mirror-image surpluses in corporate profits, as a share of GDP. This is not only true in terms of levels but in terms of changes. That is, the change in combined government and household savings over periods of say, 3-4 years is also closely mirrored by changes in corporate profits in the opposite direction. This isn’t even a theory – it’s largely driven by accounting identities and economic equilibrium.

Again, the difficulty with valuing stocks on the basis of raw price/earnings ratios is that corporate profits as a share of GDP are presently over 70% above their long-term historical norm. Though the actual course of corporate profits will be affected by numerous factors, including the extent to which extraordinary fiscal deficits normalize, we would expect corporate profits over the coming 3-4 year period to contract at a rate of somewhere between 5-15% annually. The practice of valuing stocks on the basis of current earnings or Wall Street’s projections of “forward operating earnings” (which embed assumptions of even more extreme profit margins) hasnever in history been more reckless and misleading.

One hardly needs to accept any of these concerns to recognize that current equity valuations are consistent with the likelihood of dismal long-term returns. The historical record of reliable valuation measures should be sufficient. The chart below illustrates the relationship between the S&P 500 price/revenue ratio and subsequent 10-year nominal annual total returns for the S&P 500.

Last week, much was made of a remark by Warren Buffett that he was having difficulty finding any bargains in the current market. In our view, he did not go far enough, because even his more recent comments about valuation seem inconsistent with his own very accurate observations in the past. For example, Buffett noted in 1999 that “In my opinion, you have to be wildly optimistic to believe that corporate profits as a percent of GDP can, for any sustained period, hold much above 6%.” That assertion was clearly demonstrated by the clearly cyclical behavior of margins in the years that followed. It’s an assertion that deserves particular attention today.

Read the complete commentary