One of the themes that I want to explore in some depth is “pure” contrarian investing, which is investing relying solely on the phenomenon of reversion to the mean. I’m calling it “pure” contrarian investing to distinguish it from the contrarian investing that is value investing disguised as contrarian investing. The reason for making this distinction is that I believe Lakonishok, Shleifer, and Vishny’s characterization of the returns to value as contrarian returns is a small flaw in Contrarian Investment, Extrapolation and Risk. I argue that it is a problem of LSV’s definition of “value.” I believe that LSV’s results contained the effects of both pure contrarianism (mean reversion) and value. While mean reversion and value were both observable in the results, I don’t believe that they are the same strategy, and I don’t believe that the returns to value are solely due to mean reversion. The returns to value stand alone and the returns to a mean reverting strategy also stand alone. In support of this contention I set out the returns to a simple pure contrarian strategy that does not rely on any calculation of value.

Contrarianism relies on mean reversion

The grundnorm of contrarianism is mean reversion, which is the idea that stocks that have performed poorly in the past will perform better in the future and stocks that have performed well in the past will not perform as well. Graham, quoting Horace’s Ars Poetica, described it thus:

Many shall be restored that now are fallen and many shall fall that are now in honor.

LSV argue that most investors don’t fully appreciate the phenomenon, which leads them to extrapolate past performance too far into the future. In practical terms it means the contrarian investor profits from other investors’ incorrect assessment that stocks that have performed well in the past will perform well in the future and stocks that have performed poorly in the past will continue to perform poorly.

LSV’s definition of value is a problem

LSV’s contrarian model argues that value strategies produce superior returns because of mean reversion. Value investors would argue that value strategies produce superior returns because they are exchanging of one store of value (say, 67c) for a greater store of value (say, a stock worth say $1). The problem is one of definition.

In Contrarian Investment, Extrapolation and Risk LSV categorized the stocks on simple one-variable classifications as either “glamour” or “value.” Two of those variables were price-to-earnings and price-to-book (there were three others). Here is the definitional problem: A low price-to-earnings multiple or a low price-to-book multiple does not necessarily connote value and the converse is also true, a high price-to-earnings multiple or a high price-to-book multiple does not necessarily indicate the absence of value.

John Burr Williams 1938 treatise The Theory of Investment Value is still the definitive word on value. Here is Buffett’s explication of Williams’s theory in his1992 letter to shareholders, which I use because he puts his finger right on the problem with LSV’s methodology:

Pure contrarianism

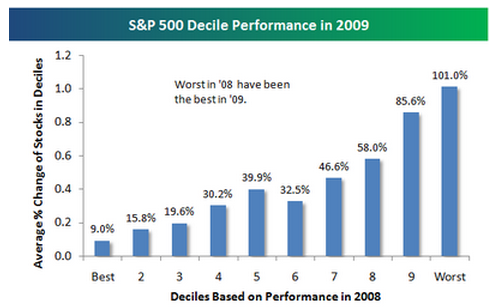

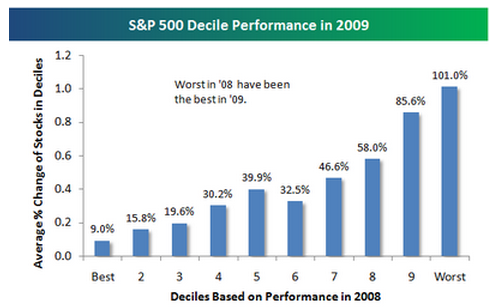

Pure contrarian investing is investing relying solely on the phenomenon of reversion to the mean without making an assessment of value. Is it possible to observe the effects of mean reversion by constructing a portfolio on a basis other than some indicia of value? It is, and the Bespoke Investment Group has done all the heavy lifting for us. Bespoke constructed from the S&P500 ten portfolios with 50 stocks in each on the basis of stock performance in 2008. They then tracked the performance of those stocks in 2009. The result?

It’s a stunning outcome, and it seems that the portfolios (almost) performed in rank order. While there may be a value effect in these results, the deciles were constructed on price performance alone. This would seem to indicate that, at an aggregate level at least, mean reversion is a powerful phenomenon and a pure contrarian investment strategy relying on mean reversion should work.

Greenbackd

http://greenbackd.com/

Contrarianism relies on mean reversion

The grundnorm of contrarianism is mean reversion, which is the idea that stocks that have performed poorly in the past will perform better in the future and stocks that have performed well in the past will not perform as well. Graham, quoting Horace’s Ars Poetica, described it thus:

LSV argue that most investors don’t fully appreciate the phenomenon, which leads them to extrapolate past performance too far into the future. In practical terms it means the contrarian investor profits from other investors’ incorrect assessment that stocks that have performed well in the past will perform well in the future and stocks that have performed poorly in the past will continue to perform poorly.

LSV’s definition of value is a problem

LSV’s contrarian model argues that value strategies produce superior returns because of mean reversion. Value investors would argue that value strategies produce superior returns because they are exchanging of one store of value (say, 67c) for a greater store of value (say, a stock worth say $1). The problem is one of definition.

In Contrarian Investment, Extrapolation and Risk LSV categorized the stocks on simple one-variable classifications as either “glamour” or “value.” Two of those variables were price-to-earnings and price-to-book (there were three others). Here is the definitional problem: A low price-to-earnings multiple or a low price-to-book multiple does not necessarily connote value and the converse is also true, a high price-to-earnings multiple or a high price-to-book multiple does not necessarily indicate the absence of value.

John Burr Williams 1938 treatise The Theory of Investment Value is still the definitive word on value. Here is Buffett’s explication of Williams’s theory in his1992 letter to shareholders, which I use because he puts his finger right on the problem with LSV’s methodology:

In The Theory of Investment Value, written over 50 years ago, John Burr Williams set forth the equation for value, which we condense here: The value of any stock, bond or business today is determined by the cash inflows and outflows – discounted at an appropriate interest rate – that can be expected to occur during the remaining life of the asset. Note that the formula is the same for stocks as for bonds. Even so, there is an important, and difficult to deal with, difference between the two: A bond has a coupon and maturity date that define future cash flows; but in the case of equities, the investment analyst must himself estimate the future “coupons.” Furthermore, the quality of management affects the bond coupon only rarely – chiefly when management is so inept or dishonest that payment of interest is suspended. In contrast, the ability of management can dramatically affect the equity “coupons.”What LSV observed in their paper may be attributable to contrarianism (mean reversion), but it is not necessarily attributable to value. While I think LSV’s selection of price-to-earnings and price-to-book as indicia of value in the aggregate probably means that value had some influence on the results, I don’t think they can definitively say that the cheapest stocks were in the “value” decile and the most expensive stocks were in the “glamour” decile. It’s easy to understand why they chose the indicia they did: It’s impractical to consider thousands of stocks and, in any case, impossible to reach a definitive value for each of those stocks (we would all assess the value of each stock in a different way). This leads me to conclude that the influence of value was somewhat weak, and what they were in fact observing was the influence of mean reversion. It doesn’t therefore seem valid to say that the superior returns to value are due to mean reversion when they haven’t tested for value. It does, however, raise an interesting question for investors. Can you invest solely relying on reversion to the mean? It seems you might be able to do so.

The investment shown by the discounted-flows-of-cash calculation to be the cheapest is the one that the investor should purchase – irrespective of whether the business grows or doesn’t, displays volatility or smoothness in its earnings, or carries a high price or low in relation to its current earnings and book value. Moreover, though the value equation has usually shown equities to be cheaper than bonds, that result is not inevitable: When bonds are calculated to be the more attractive investment, they should be bought.

Pure contrarianism

Pure contrarian investing is investing relying solely on the phenomenon of reversion to the mean without making an assessment of value. Is it possible to observe the effects of mean reversion by constructing a portfolio on a basis other than some indicia of value? It is, and the Bespoke Investment Group has done all the heavy lifting for us. Bespoke constructed from the S&P500 ten portfolios with 50 stocks in each on the basis of stock performance in 2008. They then tracked the performance of those stocks in 2009. The result?

Many of the stocks that got hit the hardest last year came roaring back this year, and the numbers below help quantify this. As shown, the 50 stocks in the S&P 500 that did the worst in 2008 are up an average of 101% in 2009! The 50 stocks that did the best in 2008 are up an average of just 9% in 2009. 2009 was definitely a year when buying the losers worked.

It’s a stunning outcome, and it seems that the portfolios (almost) performed in rank order. While there may be a value effect in these results, the deciles were constructed on price performance alone. This would seem to indicate that, at an aggregate level at least, mean reversion is a powerful phenomenon and a pure contrarian investment strategy relying on mean reversion should work.

Greenbackd

http://greenbackd.com/