This is the submission from Henry W. Schacht, CFA for our Value Idea Contest. - Editor's note.

To say that this author is reticent about investing in France is an understatement. After all, this is the home of the 35-hour work week and other similarly “enlightened” economic policies. In spite of this, there are French firms that are relevant on the world stage.

Vivendi (VIV.PA, Financial) is one shining example, but few investors seem to have noticed.

In spite of this (or perhaps because of it), Vivendi is the subject of this bullish report. The company provides attractive exposure to media and telecom in both developed and emerging markets. Investors should benefit from the disappearance of a conglomerate discount as Vivendi’s corporate structure simplifies and its true identity comes into greater focus. Perhaps most importantly, Vivendi is cheap, offering investors a low free cash flow multiple and a dividend yield that will make grown men tear up with joy, making the wait for the aforementioned catalysts a lot less painful.

It comes as no surprise that this investment thesis will be met with skepticism by those with a sense of history.

Vivendi began its life as Compagnie Générale des Eaux (CGE), a water utility, in 1853. It remained a boring utility well into the 20th century, when it caught the conglomerate bug. It was an infection that afflicted many firms - including Coca-Cola, which felt compelled to buy Columbia Pictures in 1982.

Once it started down this road, CGE felt compelling to change its name in 1988, ostensibly to reflect the changing nature of the company’s business. This author has long believed that name changes are a major red flag for investors. The "new" Vivendi proved the theory. While Coca-Cola got back to basics after only a decade of "diversifying", Vivendi’s search for ever sexier businesses lasted until 2002 when then-CEO Jean-Marie Messier resigned in disgrace.

An orgy of debt-fueled deals left Vivendi an unwieldy mess, a company dabbling in everything from books to booze. The debt was staggering and so was the company… staggering towards bankruptcy. Worse, Vivendi had no sense of its own identity. By extension, neither did its shareholders.

The exclamation point on the entire sordid affair came in 2002 when the company disclosed a loss of €23.3 billion. It was Vivendi’s AOL Time Warner moment (AIG, maybe?). In any case, the loss is the worst ever for a French company.

Richard Chesnoff ’s book The Arrogance of the French: Why They Can't Stand Us--and Why the Feeling Is Mutual came out in 2005. It isn’t hard to imagine that Chesnoff’s motivation had something to do with his being a disgruntled Vivendi shareholder.

came out in 2005. It isn’t hard to imagine that Chesnoff’s motivation had something to do with his being a disgruntled Vivendi shareholder.

Ready to invest yet?

If this past doesn’t give you the warm-and-fuzzies, it is completely understandable. That said, these experiences fall under the heading of “what doesn’t kill you can make you stronger”. And Vivendi has learned from its near-death experience. The transformation started shortly after Mr. Messier was shown the door.

Indeed, the final chapter of this French tragedy is being written with a massive shareholder lawsuit moving through the courts. Resolution for many of these legal issues should be seen within the next year or so. The company has taken a charge to cover potential liabilities. While some may view any legal issue as a negative, we believe the conclusion of this litigation will be a major positive catalyst for patient investors. The collective sigh of relief from investors will be palpable, even if the price tag is significant.

Further enumeration of Vivendi’s past sins would consume countless pages without adding much more to this analysis. Suffice it to say that European stocks are out of favor these days, but even among this group of black sheep, Vivendi remains an outcast. It is obvious that Vivendi’s negative image is well-deserved given its checkered past. So the bias against the company is based in truth, even if it is no longer relevant. Nonetheless, the impression that Vivendi is a place where assets go to die is alive and well. Herein lays the opportunity for current investors.

This picture of Vivendi’s past is admittedly incomplete, because frankly it is easy to dwell on what Vivendi was and allow that to color one’s opinion. To get a view of just how cheap this chastened giant really is, it is more important to know what Vivendi is today and to understand where its management intends to lead.

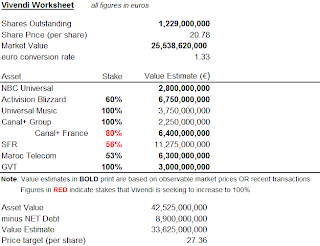

Vivendi’s current market value is 25 billion euros (or $33 billion). For this purchase price, would-be buyers get: a 12% stake in NBC Universal, 60% ownership in Activision Blizzard (ATVI), 53% of Maroc Telecom (Morocco), 56% of SFR (a French telecom), 100% of GVT (a Brazilian telecom), Canal+ Group, Universal Music, and lastly 80% of Canal+ France, a French cable TV & film company.

Despite its continuing quest for greater simplicity, at present, Vivendi doesn’t make for tidy spreadsheets. Public assets join non-public ones and those denominated in dollars meet those that are no. There are wholly-owned subsidiaries (Universal Music and GVT) and partially owned ones (Activision). And everything is consolidated onto Vivendi’s books. When they call it the Vivendi “GROUP”, they aren’t kidding.

When trying to get a handle on what Vivendi is worth, it may be helpful to come at the answer from 2 directions. The first is a sum of the parts analysis. The other is by getting an idea of Vivendi’s net income and free cash flow. Keep in mind that not all cash flows up to the parent company. Activision is an example. Relative to its overall earnings, ATVI pays a very modest dividend, preferring instead to focus on expansion and share repurchases. Nonetheless, the earnings power of ActivisionActivision.

The current value of that Activision stake is roughly $9 billion. The other subsidiary that is publicly traded is Maroc Telecom (IAM.PA). Vivendi’s majority stake in this Moroccan telecom is worth about 6 billion euros ($8 billion). Worlds apart in all respects, these two holdings are among the most easily valued of Vivendi’s businesses. Their values are also growing thanks (in part) to increasing sales and profits.

In the case of Activision, the value proposition has been made plain for all to see. Vivendi helped create ATVI in 2008. At that point, Vivendi owned 52 percent of the combined entity. Thanks to Activision’s persistent and effective share repurchases, however, that stake has steadily grown in relative and absolute value. We believe that is likely to continue.

The publicly traded components of Vivendi sum to a respectable, $17 billion of combined market value. Not bad, considering they are not significant cash flow generators for Team Vivendi.

SFR and Canal + are the cash cows pulling Vivendi’s wagon these days. SFR accounted for over 40% of Vivendi’s EBITA for the 9 months ending September 30th. That’s nearly 2 billion euros in just 9 months out of a total of 4.7 billion euros. This French telecom firm is 44% owned by Vodafone (VOD, Financial), but Vivendi is the controlling shareholder.

It is said that Vodafone wants to sell its SFR stake. For the right price, of course. Vivendi has also made no secret that it would like to bring SFR into the Vivendi tent in its entirety. In fact, as recently as November, CEO Jean-Bernard Levy said that taking full control of SFR was a top priority for Vivendi. Price estimates for Vodafone’s SFR stake range from 6 to 9 billion euros, placing the value of Vivendi’s existing stake as high as $15 billion. Given the values being placed on Vivendi’s other holdings, SFR seems undervalued even at this level. This analyst believes the consolidation of SFR would eliminate a significant source of conglomerate discount.

The other major source of this discount is Canal+. While Vivendi owns 100% of Canal+ Group and its mixture of content/cable/satellite assets, including Studio Canal (which owns the world’s 3rd largest firm library), Cyfra+ , iTele, and Canal Overseas (with its exposure to Africa, Vietnam & other territories), it only owns 80% of Canal’s largest asset – Canal+ France.

Vivendi has been systematically buying out other Canal+ France shareholders in recent years, including 5.1% acquired in February. This transaction price generated an implied value for Vivendi’s 80% stake of nearly $8 billion.

The last piece of the Canal+ France pie is owned by another French conglomerate firm called Lagardere. Following the most recent 5.1% deal, Lagardere asked for the equivalent of $9 billion for its 20% stake. With its newfound price sensitivity, Vivendi balked and walked. Lagardere is now trying to play hardball by threatening an IPO of its shares. One analyst termed the move an “ineffective threat”, saying that Vivendi isn’t in any hurry. Time will tell.

As the majority stakeholder in both Canal+ and SFR, Vivendi is the most logical buyer (and the one most likely to pay the highest price). It is a measure of Vivendi’s patience and discipline that one or both of these deals has not already been done. As such, we view these deals as positive future catalysts with the potential to eliminate large portions of Vivendi’s conglomerate discount.

The last remaining wholly-owned Vivendi assets are GVT and Universal Music, the largest owner of record labels in the industry. While some may see this as a business in decline, Universal is a solid cash generator and provides insight into the Vivendi blueprint. In 2006, Vivendi bought out Universal Music’s minority shareholder (Matsushita) and in 2007 they bought competitor BMG. Industry worries aside, Universal is a likely a core Vivendi holding, worth around $5billion.

GVT is the Brazilian telecom that Vivendi bought earlier this year. They outbid Spain’s Telefonica (TEF, Financial) in order to gain a foothold in Brazil’s fast-growing telecommunications market. The bidding process and the resulting $4.2 billion price tag almost guarantee that Vivendi overpaid for GVT. That said, GVT is one of Vivendi’s main growth drivers. 2009 revenues came in at $1 billion. By 2014, that figure is expected to triple according to the company. Telefonica’s losing bid amounted to $3.7 billion. Given GVT’s subsequent growth, it seems reasonable that the private market value of this subsidiary remains between $3.7 and $4.2 billion.

If this considerable list of assets needed an afterthought, NBC Universal is it. Vivendi’s stake in this media giant has been sold to GE/Comcast for $5.8 billion of which $2 billion has already been received. The remaining $3.8 billion is expected soon. At that price, it’s quite an afterthought. (Update)

In addition to these businesses, Vivendi has net debt (as of Sept 30) of 8.9 billion euros. Not bad considering it is less than the market value of Vivendi’s Activision stake, certainly not the staggering load from days gone by. In fact, management expects net debt to fall to 6.5 billion euros by calendar year-end 2010 (assuming the NBC deal is completed as scheduled). The disposal of this business will further simplify Vivendi’s structure. Hopefully investor interest and understanding will follow.

With the possible exception of Universal Music, cable and telecom properties make up the core of the “new” Vivendi. Vivendi knows who and what they are. No more flailing around for direction either, they know where they want to go. The company has the wherewithal to buy out their remaining minority shareholders if/when the stakes become available.

The NBC Universal proceeds, extraordinary free cash flow, and (if needed) additional debt capacity make for a lot of possibilities. In the meantime, investors can afford to be patient.

Dividends may have been considered passé in the Messier era, but not today. Vivendi paid a dividend of 1.40 euros per share on May 11, 2010 that was based on its fiscal 2009 results. This isn’t a one-time thing. A 1.40 euro dividend per share was also paid in 2009 for 2008 results. Indeed, prior dividends paid include 1.30 euro paid in May 2008 and 1.20 euros paid in April 2007. Nonetheless, investors seem unaware of Vivendi’s history of significant dividends.

The 1.40 euro payout implies a yield of nearly 7 percent! And Vivendi has already committed to maintaining that 1.40 euro payout in 2011. Better buy some shares before April or May!

Vivendi’s dividend is calculated based on the prior year’s results, so without an exact idea of how much cash is making its way to the parent company, the dividend payment is a good starting point. This free cash flow proxy plus the equity values of those companies that aren’t paying cash flow to HQ imply a value for Vivendi of between $45 and $50 billion. This results in a share price of $35 to $40 (26 to 30 euros).

The company tries to help investors get an idea of its earnings power by publishing an “adjusted net income” figure. Investors are right to be skeptical of so-called pro-forma numbers, but given the other data points, Vivendi’s calculation looks reasonable. For fiscal year 2009, Vivendi reported 2.6 billion euros in adjusted net income. Warren Buffett often speaks of the look-through earnings of Berkshire Hathaway holdings like Coca-Cola. Vivendi’s adjustments are along these same lines. Taken at face value, Vivendi trades at a modest 9-10 times this adjusted number.

A pure sum-of-the-parts view probably would point investors to the lower end of the valuation range (see insert), while a cash flow perspective should skew the results toward the high end. Investors can (and will) differ on the relative value of Vivendi’s various parts, but the economic weight of the whole should be quite evident.

Today, investors will find a company whose strategy is well defined: to exit non-core businesses (like NBC Universal), to expand core businesses organically and via acquisition, while sharing the wealth with shareholders. Rather than frantically doing deals for the sake of the deal, Vivendi’s near-term goal is to eliminate minority owners and rid itself of the conglomerate label and its associated discounts. One can clearly see that the current situation at Vivendi is a direct response to (and refutation of) its unpleasant past. It is a stark contrast indeed.

But Vivendi is still a French company. And as such, it sometimes sends mixed messages and often rubs people the wrong way. Compare and contrast the lucid and compelling investor presentation we have included with the company’s byzantine website, which seems to mirror the complexity of the old Vivendi web of subsidiaries.

Furthermore, the company recently announced that it has canceled its sponsored ADR program (old ticker: VIVDY). When asked for an explanation, the company responded simply: “Vivendi has decided it no longer wants to sponsor a program in the United States.” Pressed for the reason why, a Vivendi representative elaborated (somewhat). The response: “The Level One ADR program is very small, far less than 1% of shares outstanding. There didn’t seem to be much interest in the Level One ADR program in the U.S. as compared to owning the common shares which trade in Paris.”

The author is now refraining from making any French jokes referencing retreat. Suffice it to say that wherever it is traded, Vivendi is a bargain at the current price. And despite all its issues and quirks, investors should take a look at Vivendi and its reformation.

In the past, Vivendi could easily have had its own chapter in another ecumenical book – 50 Reasons to Hate the French. But perhaps some reconciliation is in order. Chapter 3 of Mr. Chesnoff’s book is entitled: A Long Legacy of Love and Hate.

Where Vivendi is concerned there has been plenty of(well-deserved) hate. It’s time for some love.

Vive Vivendi!

The Messier era is dead.

Disclosure: Author is long Vivendi, Vodafone, and Telefonica.

To say that this author is reticent about investing in France is an understatement. After all, this is the home of the 35-hour work week and other similarly “enlightened” economic policies. In spite of this, there are French firms that are relevant on the world stage.

Vivendi (VIV.PA, Financial) is one shining example, but few investors seem to have noticed.

In spite of this (or perhaps because of it), Vivendi is the subject of this bullish report. The company provides attractive exposure to media and telecom in both developed and emerging markets. Investors should benefit from the disappearance of a conglomerate discount as Vivendi’s corporate structure simplifies and its true identity comes into greater focus. Perhaps most importantly, Vivendi is cheap, offering investors a low free cash flow multiple and a dividend yield that will make grown men tear up with joy, making the wait for the aforementioned catalysts a lot less painful.

It comes as no surprise that this investment thesis will be met with skepticism by those with a sense of history.

Vivendi began its life as Compagnie Générale des Eaux (CGE), a water utility, in 1853. It remained a boring utility well into the 20th century, when it caught the conglomerate bug. It was an infection that afflicted many firms - including Coca-Cola, which felt compelled to buy Columbia Pictures in 1982.

Once it started down this road, CGE felt compelling to change its name in 1988, ostensibly to reflect the changing nature of the company’s business. This author has long believed that name changes are a major red flag for investors. The "new" Vivendi proved the theory. While Coca-Cola got back to basics after only a decade of "diversifying", Vivendi’s search for ever sexier businesses lasted until 2002 when then-CEO Jean-Marie Messier resigned in disgrace.

An orgy of debt-fueled deals left Vivendi an unwieldy mess, a company dabbling in everything from books to booze. The debt was staggering and so was the company… staggering towards bankruptcy. Worse, Vivendi had no sense of its own identity. By extension, neither did its shareholders.

The exclamation point on the entire sordid affair came in 2002 when the company disclosed a loss of €23.3 billion. It was Vivendi’s AOL Time Warner moment (AIG, maybe?). In any case, the loss is the worst ever for a French company.

Richard Chesnoff ’s book The Arrogance of the French: Why They Can't Stand Us--and Why the Feeling Is Mutual

came out in 2005. It isn’t hard to imagine that Chesnoff’s motivation had something to do with his being a disgruntled Vivendi shareholder.

came out in 2005. It isn’t hard to imagine that Chesnoff’s motivation had something to do with his being a disgruntled Vivendi shareholder. Ready to invest yet?

If this past doesn’t give you the warm-and-fuzzies, it is completely understandable. That said, these experiences fall under the heading of “what doesn’t kill you can make you stronger”. And Vivendi has learned from its near-death experience. The transformation started shortly after Mr. Messier was shown the door.

Indeed, the final chapter of this French tragedy is being written with a massive shareholder lawsuit moving through the courts. Resolution for many of these legal issues should be seen within the next year or so. The company has taken a charge to cover potential liabilities. While some may view any legal issue as a negative, we believe the conclusion of this litigation will be a major positive catalyst for patient investors. The collective sigh of relief from investors will be palpable, even if the price tag is significant.

Further enumeration of Vivendi’s past sins would consume countless pages without adding much more to this analysis. Suffice it to say that European stocks are out of favor these days, but even among this group of black sheep, Vivendi remains an outcast. It is obvious that Vivendi’s negative image is well-deserved given its checkered past. So the bias against the company is based in truth, even if it is no longer relevant. Nonetheless, the impression that Vivendi is a place where assets go to die is alive and well. Herein lays the opportunity for current investors.

This picture of Vivendi’s past is admittedly incomplete, because frankly it is easy to dwell on what Vivendi was and allow that to color one’s opinion. To get a view of just how cheap this chastened giant really is, it is more important to know what Vivendi is today and to understand where its management intends to lead.

Vivendi’s current market value is 25 billion euros (or $33 billion). For this purchase price, would-be buyers get: a 12% stake in NBC Universal, 60% ownership in Activision Blizzard (ATVI), 53% of Maroc Telecom (Morocco), 56% of SFR (a French telecom), 100% of GVT (a Brazilian telecom), Canal+ Group, Universal Music, and lastly 80% of Canal+ France, a French cable TV & film company.

Despite its continuing quest for greater simplicity, at present, Vivendi doesn’t make for tidy spreadsheets. Public assets join non-public ones and those denominated in dollars meet those that are no. There are wholly-owned subsidiaries (Universal Music and GVT) and partially owned ones (Activision). And everything is consolidated onto Vivendi’s books. When they call it the Vivendi “GROUP”, they aren’t kidding.

When trying to get a handle on what Vivendi is worth, it may be helpful to come at the answer from 2 directions. The first is a sum of the parts analysis. The other is by getting an idea of Vivendi’s net income and free cash flow. Keep in mind that not all cash flows up to the parent company. Activision is an example. Relative to its overall earnings, ATVI pays a very modest dividend, preferring instead to focus on expansion and share repurchases. Nonetheless, the earnings power of ActivisionActivision.

The current value of that Activision stake is roughly $9 billion. The other subsidiary that is publicly traded is Maroc Telecom (IAM.PA). Vivendi’s majority stake in this Moroccan telecom is worth about 6 billion euros ($8 billion). Worlds apart in all respects, these two holdings are among the most easily valued of Vivendi’s businesses. Their values are also growing thanks (in part) to increasing sales and profits.

In the case of Activision, the value proposition has been made plain for all to see. Vivendi helped create ATVI in 2008. At that point, Vivendi owned 52 percent of the combined entity. Thanks to Activision’s persistent and effective share repurchases, however, that stake has steadily grown in relative and absolute value. We believe that is likely to continue.

The publicly traded components of Vivendi sum to a respectable, $17 billion of combined market value. Not bad, considering they are not significant cash flow generators for Team Vivendi.

SFR and Canal + are the cash cows pulling Vivendi’s wagon these days. SFR accounted for over 40% of Vivendi’s EBITA for the 9 months ending September 30th. That’s nearly 2 billion euros in just 9 months out of a total of 4.7 billion euros. This French telecom firm is 44% owned by Vodafone (VOD, Financial), but Vivendi is the controlling shareholder.

It is said that Vodafone wants to sell its SFR stake. For the right price, of course. Vivendi has also made no secret that it would like to bring SFR into the Vivendi tent in its entirety. In fact, as recently as November, CEO Jean-Bernard Levy said that taking full control of SFR was a top priority for Vivendi. Price estimates for Vodafone’s SFR stake range from 6 to 9 billion euros, placing the value of Vivendi’s existing stake as high as $15 billion. Given the values being placed on Vivendi’s other holdings, SFR seems undervalued even at this level. This analyst believes the consolidation of SFR would eliminate a significant source of conglomerate discount.

The other major source of this discount is Canal+. While Vivendi owns 100% of Canal+ Group and its mixture of content/cable/satellite assets, including Studio Canal (which owns the world’s 3rd largest firm library), Cyfra+ , iTele, and Canal Overseas (with its exposure to Africa, Vietnam & other territories), it only owns 80% of Canal’s largest asset – Canal+ France.

Vivendi has been systematically buying out other Canal+ France shareholders in recent years, including 5.1% acquired in February. This transaction price generated an implied value for Vivendi’s 80% stake of nearly $8 billion.

The last piece of the Canal+ France pie is owned by another French conglomerate firm called Lagardere. Following the most recent 5.1% deal, Lagardere asked for the equivalent of $9 billion for its 20% stake. With its newfound price sensitivity, Vivendi balked and walked. Lagardere is now trying to play hardball by threatening an IPO of its shares. One analyst termed the move an “ineffective threat”, saying that Vivendi isn’t in any hurry. Time will tell.

As the majority stakeholder in both Canal+ and SFR, Vivendi is the most logical buyer (and the one most likely to pay the highest price). It is a measure of Vivendi’s patience and discipline that one or both of these deals has not already been done. As such, we view these deals as positive future catalysts with the potential to eliminate large portions of Vivendi’s conglomerate discount.

The last remaining wholly-owned Vivendi assets are GVT and Universal Music, the largest owner of record labels in the industry. While some may see this as a business in decline, Universal is a solid cash generator and provides insight into the Vivendi blueprint. In 2006, Vivendi bought out Universal Music’s minority shareholder (Matsushita) and in 2007 they bought competitor BMG. Industry worries aside, Universal is a likely a core Vivendi holding, worth around $5billion.

GVT is the Brazilian telecom that Vivendi bought earlier this year. They outbid Spain’s Telefonica (TEF, Financial) in order to gain a foothold in Brazil’s fast-growing telecommunications market. The bidding process and the resulting $4.2 billion price tag almost guarantee that Vivendi overpaid for GVT. That said, GVT is one of Vivendi’s main growth drivers. 2009 revenues came in at $1 billion. By 2014, that figure is expected to triple according to the company. Telefonica’s losing bid amounted to $3.7 billion. Given GVT’s subsequent growth, it seems reasonable that the private market value of this subsidiary remains between $3.7 and $4.2 billion.

If this considerable list of assets needed an afterthought, NBC Universal is it. Vivendi’s stake in this media giant has been sold to GE/Comcast for $5.8 billion of which $2 billion has already been received. The remaining $3.8 billion is expected soon. At that price, it’s quite an afterthought. (Update)

In addition to these businesses, Vivendi has net debt (as of Sept 30) of 8.9 billion euros. Not bad considering it is less than the market value of Vivendi’s Activision stake, certainly not the staggering load from days gone by. In fact, management expects net debt to fall to 6.5 billion euros by calendar year-end 2010 (assuming the NBC deal is completed as scheduled). The disposal of this business will further simplify Vivendi’s structure. Hopefully investor interest and understanding will follow.

With the possible exception of Universal Music, cable and telecom properties make up the core of the “new” Vivendi. Vivendi knows who and what they are. No more flailing around for direction either, they know where they want to go. The company has the wherewithal to buy out their remaining minority shareholders if/when the stakes become available.

The NBC Universal proceeds, extraordinary free cash flow, and (if needed) additional debt capacity make for a lot of possibilities. In the meantime, investors can afford to be patient.

Dividends may have been considered passé in the Messier era, but not today. Vivendi paid a dividend of 1.40 euros per share on May 11, 2010 that was based on its fiscal 2009 results. This isn’t a one-time thing. A 1.40 euro dividend per share was also paid in 2009 for 2008 results. Indeed, prior dividends paid include 1.30 euro paid in May 2008 and 1.20 euros paid in April 2007. Nonetheless, investors seem unaware of Vivendi’s history of significant dividends.

The 1.40 euro payout implies a yield of nearly 7 percent! And Vivendi has already committed to maintaining that 1.40 euro payout in 2011. Better buy some shares before April or May!

Vivendi’s dividend is calculated based on the prior year’s results, so without an exact idea of how much cash is making its way to the parent company, the dividend payment is a good starting point. This free cash flow proxy plus the equity values of those companies that aren’t paying cash flow to HQ imply a value for Vivendi of between $45 and $50 billion. This results in a share price of $35 to $40 (26 to 30 euros).

The company tries to help investors get an idea of its earnings power by publishing an “adjusted net income” figure. Investors are right to be skeptical of so-called pro-forma numbers, but given the other data points, Vivendi’s calculation looks reasonable. For fiscal year 2009, Vivendi reported 2.6 billion euros in adjusted net income. Warren Buffett often speaks of the look-through earnings of Berkshire Hathaway holdings like Coca-Cola. Vivendi’s adjustments are along these same lines. Taken at face value, Vivendi trades at a modest 9-10 times this adjusted number.

A pure sum-of-the-parts view probably would point investors to the lower end of the valuation range (see insert), while a cash flow perspective should skew the results toward the high end. Investors can (and will) differ on the relative value of Vivendi’s various parts, but the economic weight of the whole should be quite evident.

Today, investors will find a company whose strategy is well defined: to exit non-core businesses (like NBC Universal), to expand core businesses organically and via acquisition, while sharing the wealth with shareholders. Rather than frantically doing deals for the sake of the deal, Vivendi’s near-term goal is to eliminate minority owners and rid itself of the conglomerate label and its associated discounts. One can clearly see that the current situation at Vivendi is a direct response to (and refutation of) its unpleasant past. It is a stark contrast indeed.

But Vivendi is still a French company. And as such, it sometimes sends mixed messages and often rubs people the wrong way. Compare and contrast the lucid and compelling investor presentation we have included with the company’s byzantine website, which seems to mirror the complexity of the old Vivendi web of subsidiaries.

Furthermore, the company recently announced that it has canceled its sponsored ADR program (old ticker: VIVDY). When asked for an explanation, the company responded simply: “Vivendi has decided it no longer wants to sponsor a program in the United States.” Pressed for the reason why, a Vivendi representative elaborated (somewhat). The response: “The Level One ADR program is very small, far less than 1% of shares outstanding. There didn’t seem to be much interest in the Level One ADR program in the U.S. as compared to owning the common shares which trade in Paris.”

The author is now refraining from making any French jokes referencing retreat. Suffice it to say that wherever it is traded, Vivendi is a bargain at the current price. And despite all its issues and quirks, investors should take a look at Vivendi and its reformation.

In the past, Vivendi could easily have had its own chapter in another ecumenical book – 50 Reasons to Hate the French. But perhaps some reconciliation is in order. Chapter 3 of Mr. Chesnoff’s book is entitled: A Long Legacy of Love and Hate.

Where Vivendi is concerned there has been plenty of(well-deserved) hate. It’s time for some love.

Vive Vivendi!

The Messier era is dead.

Disclosure: Author is long Vivendi, Vodafone, and Telefonica.